INTRO

The Bordeaux wine scene is about to enter a pioneering era with the inaugural year of a new initiative for corporate responsibility that bears the name ‘Bordeaux Cultivons Demain’. This sets down a guide for environmental, economic and social responses in today’s climate, for everyone from small vignerons to grand châteaux, wine merchants to Caves Coopératives, And those choosing to adhere will be independently audited, eventually leading to the awarding of an official label. But this is just the concretisation, the tip of the iceberg, of a new responsible mentality has been taking root in Bordeaux for many years, be it for protecting biodiversity or worker’s welfare, combating climate change, diminishing not just pesticides but carbon footprint, respecting the soil, flowers, pollinators, bats and birds.

And this concerted ecological impetus has already seen a phenomenal increase in the percentage of Bordeaux vineyards with at least one certified environmental approach – be it organic, biodynamic, High Environmental Value or Terra Vitis – from 35% in 2014 to 75% in 2021. Today, just look at any châteaux winery website and there are new sections dedicated to ecology, biodiversity or agroforestry initiatives, then look around at the walls of tasting rooms and there are now a row of serious industry certifications alongside the usual gold medal diplomas from wine competitions. This Trail takes a tour of the 7 of the pioneers of this new philosophy, each one with a different story to tell.

This stunning Renaissance château, which dates back some 800 years, is a landmark stop for wine lovers visiting the Bordelais, both for its palatial interiors and wines aged in stunning subterranean grottoes that stretch for 25 kilometres below the castle. Situated in the heart of the Fronsac appellation, overlooking a 65 hectares vineyard and the Dordogne river, the domaine had been overseen for 25 years by its genial director and oenologue, Xavier Buffo, who has long been at the vanguard of implementing social and environmental initiatives.

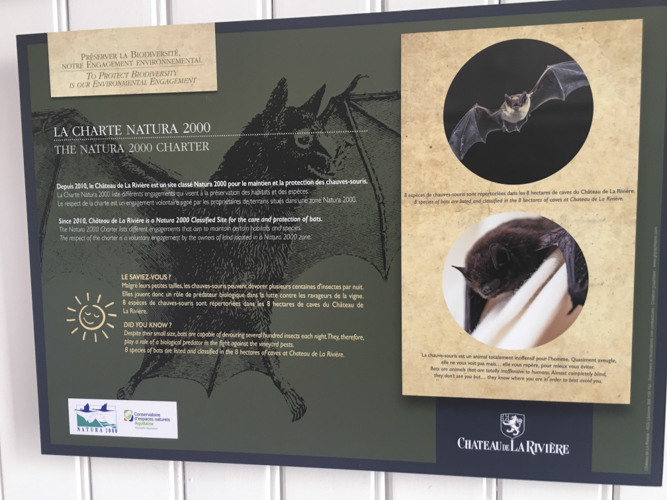

The château’s 20,000 annual visitors are given an educational explanation of projects like Natura 2000 that safeguard bats, the perfect natural insect repellent, as there 8 rare species nesting in the cellar caves, as well as the protection of biodiversity through planting hedgerows, fruit trees and leaving swathes of their woodlands wild to attract vital pollinators like wild bees. But his greatest efforts have concentrated on aiding the local community. “I wanted a project that could involve local villages, businesses and neighbouring wine makers,” explains Xavier, “while at the same time giving widespread publicity to La Rivière.

The solution was Le Confluent d’Arts, our very own festival. The first one was in 2017, headlined by a famous-name musician to attract attention, numerous local bands and singers, street theatre even inside the chateau itself, food trucks and a wine bar showcasing all the winemakers in our commune. We ask schools to participate with a project to decorate the château, and around 60 locals volunteers help run the festival. It is genuine community effort, drawing 6,500 people”

This perfectly preserved 17th century château dates back to 1750 when it was one of the homes of the wife of King Louis XV, hence its name.

Today La Dauphine is surrounded by a 66 hectare certified organic vineyard, producing elegant Fronsac wines, making use of a creative mix of raw concrete tanks and terracotta amphorae. The estate’s director, Stéphanie Barousse, enthuses about their signature, highly original project that perfectly illustrates the three pillars of Bordeaux Cultivons Demain; Environment, Social, Economic.

”We have revived the ancient tradition of “transhumance”, bringing a flock of 200 sheep down from the Pyrénées, along with their shepherd. They stay in our vineyards from October to May, eating all the vineyard weeds while leaving their natural, ecological manure for fertiliser, while to reduce carbon footprint, we do not use the tractor. From the social side, well the sheep certainly bring a smile to our workers faces, it brings us in touch with local villages who all want to see the sheep in action, while it permits the shepherd economically to work the whole year rather than taking an alternative second winter job. And then there is economic. Obviously we no longer need to buy manure to fertilise the soil, while the breeder saves money as these are young sheep that neither give milk nor reproduce yet, so it stops them being an economic burden. We work with five breeders and this pilot year has been such a success that next year it will be 400 sheep and 8-10 neighbouring châteaux have told us that they would like to participate too.” The château is closely involved with surrounding villages, trying to recruit young locals as workers while organising regular school visits, alongside a host of simple but important daily actions; raising chicken to save food waste, building bee hives, and improving vineyard working conditions by providing effective earplugs and protective glasses.

Imbetween Saint-Emilion and Lussac, the Rousseau family’s modern cellar vinifies and ages wines from 5 different chateaux, spanning Pomerol, Lalande Pomerol and Lussac alongside a large production of Bordeaux Superior, totalling some 400,000 bottles in all. The cosy tasting room resembles most Bordeaux châteaux, with a wall proudly covered with official-looking certificates, but instead of announcing wine competition medals, as is usually the case, these are all recognition of initiatives related to Corporate Social Responsibility.

Winemaker Laurent Rousseau proudly shows of his qualifications for the sustainable measures of Terra Vitis and HVE, High Environmental Value, as well as Professional Equality and Diversity in the Workplace and one rarely seen in wineries, for Food and Safety. He explains that, “these initiatives have had a very positive effect on my business. The Food and Safety certificate has literally opened up the United Sates, where I now sell a large part of my 300,000 bottles of Bordeaux Supérior, because an importer there can place them in a major supermarket chain that insists on this regulation.”

The winery is a pioneer in the treatment of its dirty water effluence, used to irrigate a huge plot of bamboo, creating compost and encouraging biodiversity. And on a purely human scale, Laurent has a long history with the local community aiding reinsertion of handicapped people into working life. “The concept,” he explains, “is that handicapped people, mental or physical, from a local centre, are given the chance to be useful in our workplace, allowing them to finally discover some self-respect. So they work in the vine, pruning and harvesting, while in the cellar they help with packaging and labelling. They do what they can, when they can. While one of my workers might take 300 minutes to label 600 bottles, it can take four of them all day. No matter, they have their place in our workforce.”

In the heart of the Médoc’s Saint-Estèphe appellation, this imposing château is imbued with history since its vineyard was planted by Irish wine merchant Bernard O’Phelan in 1805. While Bordeaux oenologue Michel Rolland still consults on their wines, the day-to-day running of the château has long been overseen by Véronique Dausse and cellar master, Fabrice Bacquey, who for many years have instigated actions both to protect the estate’s biodiversity and develop agroforestry through the planting of hedges and trees.

In terms of social initiatives, Phélan Ségur have enthusiastically participated in Les Vignerons du Vivant, a projects to attract new people to work in the world of wine. After demonstrating simple but essential social skills – punctuality, politeness, respect – candidates must pass a three month trial period to see if they are ready to work and live as a vigneron, then stay for 12 months that combine an immersion in the daily life of the estate, complemented by a series of in-depth meetings with experts in environmental fields ranging from biodynamics, working the soil and plants, sustainability, nourishing the vine.

Lolita Tyl, originally from Paris, completed the course, received both her certificate and was awarded a job at the château. She reflects that, “it was the perfect way to discover if I liked the life of a winemaker, while gaining knowledge and skill at the same time. For sure, not everyone can handle this kind of work, but I love it and want to stay on here. I enjoy working in the cellar, but my dream would be to become a ‘chef de culture’. That is what was great about the course – it opens your eyes to biodiversity and sustainability, you get to be mentored by amazing experts, and all that is very different from how you are taught at a normal oenology or agricultural school” And Véronique enthusiastically adds that, “what this project creates is not just a job but a vocation, which is what we need in the wine making industry.”

Castel Frères Blanquefort Bordeaux

The world of Bordeaux wine is by no means limited to grand châteaux, independent vignerons and smallholder Caves Coopératives. There are also the historic ‘négociants’ wine merchants, who are responsible for producing and marketing millions of bottles of Bordeaux wine. The family-owned Castel Frères operates both as a merchant and vigneron, but their vast operation in the industrial zone of Blanquefort is where the company has been active as a founder member of the committee formulating the Bordeaux Cultivons Demain guide.

Some 300 people are employed at the plant, which can process 15 million bottles a year, stocking some 50,000 barrels, while over 200 winemakers supply them with wine. Stéphane Mischler is responsible for these initiatives and outlines how, “we accompany our vignerons right from the vineyard to the cellar. Accompany in the sense of the physical presence of our own oenologues giving advice, and as a company by persuading them to work in an environmentally-responsible manner. Concretely, we ask them to adhere to Terra Vitis certification, in our opinion, the only specifically vineyard cultivation certificate, in contrast to classic organic certification which covers to all elements of agriculture. Terra Vitis also addresses the important issues of water consumption, carbon footprint, and social issues.” For the Blanquefort workforce, the company has set up 4 action groups to develop social ideas. Everyone is a volunteer, ranging from an office secretary, to a worker on the bottling line or a cellar man.

“We call each one a Tribu, named after a grape variety,” explains Stephane, “so Sauvignon tackles the issue of training, while Merlot thinks up ideas to socialise with our suppliers, like inviting 70 of our vignerons for a convivial tasting in the barrel room.

And Petit Verdot looks at biodiversity in the workplace, which we are increasingly vegetalisizing; growing vines on the rooftop, creating insect boxes, developing a picnic area among the trees growing outside the factory.”

When the Japanese whisky giant, Suntory, bought this signature Saint-Julien château in 2003, they began 40 years of investment and commitment. Today an immaculate 142 hectare vineyard is entirely harvested by hand while virtually each individual parcel is vinified in its own stainless steel vat before blending. The dynamic young director, Benjamin Vimal, testifies that Suntory is a company that has always respected its corporate social responsibilities. “But taking part in developing the Bordeaux Cultivons Demain guide has made me rethink many things, allowing me to learn collectively from people running other wineries, such as one that is expert at managing the consumption of water.”

Benjamin has prioritised the classic problem of chronic back pain of vineyard workers, describing how “we recommend physically warming up muscles in the morning, like a sportsman, and now propose Exoskeletal jackets, that may resemble Robocop but really support the bottom of your back. The vest costs us around €1000, but there is much less sick leave.” Lagrange is also one of the founding Médoc châteaux for the Ecole de la Vigne, the Vineyard School, project. Benjamin reiterates the problem cited in every vineyard, “that it is always difficult to find people to work on a wine estate, and the School has been a very successful solution. We specifically targeted the local community, people who might never have thought about working at a wine château. A 2 year commitment offers the chance to learn skills, to get a certificate, and most importantly to get a job at the end.”

One of Benjamin’s present team, Julien Charbleytou, comes from the School’s programme. “I worked as a stone mason in Bordeaux and now I am a qualified tractor driver out in the vineyards. They even let me help out in the cellar as well, so who knows where I will end up in the future.”

Most people living in Bordeaux have no idea there is a genuine château vineyard right inside the city limits, but then this is a winery unlike others for many reasons. The château was producing wine back in the 18th century, but was acquired by the military in 1920, who pulled up the vineyard. A century later, with the land still officially in the Pessac-Léognan appellation, local community pressure stopped plans for building redevelopment, and the estate was purchased by the Ecole Sciences Agro of Bordeaux. They replanted a 23 hectare vineyard, used today both as a living laboratory for their students and commercial winery. Pierre Darriet has been the director since the beginning, and stresses that, “our vineyard is in the centre of the city, but we have only been here since 2000 and are the newcomers, arriving after the creation of a modern urban development. So our immediate aim was to communicate and interact with the local population.

Just look out of the window from the tasting room – the view is directly onto the vines where neighbours are always walking their dogs, jogging or hiking. Everyone has a genuine access through the vineyard. We email locals explaining our plans for sustainability, and put up warning flags well before we start doing vineyard treatments.

And we will soon create a vegetable garden providing quality food for surrounding kindergardens, and work alongside a local conservatory to protect the local breed of Landes ponies by putting aside 4 hectares for them to graze on. And let me stress, this is no greenwashing project created for photo-opportunities, as we plan a long-term association with the conservatory by adding goats, donkeys and sheep to our polyculture.” Pierre is clearly concerned about future environmental problems, and admits that “my biggest concern for the future the unsexy issue of controlling and diminishing our consumption of energy. So I am proud that we sell 40% of our production locally in the Gironde area. So no huge carbon footprint like exporting to USA or Japan.”

WHERE TO EAT

More than a restaurant, the Casa Gaïa is whole project devoted to sustainable, organic, seasonal cuisine; a genuine ‘locavore’ philosophy where the kitchen works directly with local farmers, fishermen, cheese and wine makers.

This relaxed cantina in the centre of Bordeaux proposes an ever-changing menu with dishes like wood-roasted locally-fished octopus served with a creamy chickpea purée.

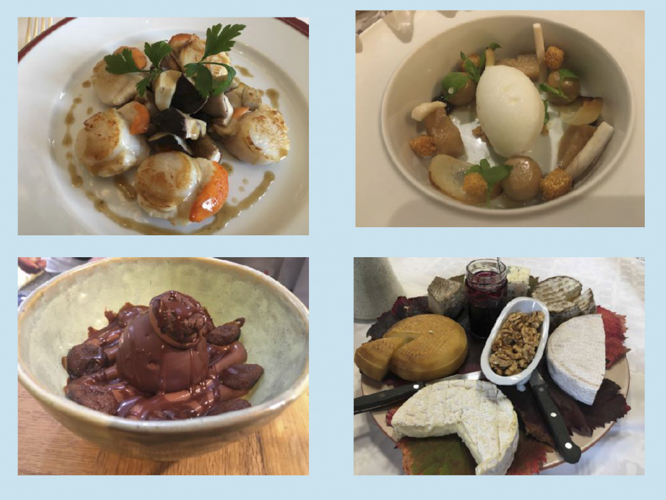

One of the top new foodie addresses to open in Bordeaux, the relaxed ambiance of this casual diner belies the research the chef Romain Corbière has done to create dishes that can work perfectly as sharing plates and also are perfectly complemented but the sommelier’s wine pairing suggestions; stingray and caper salad with a fruity Bordeaux Blanc, a to-die-for chocolate dessert and a luscious glass of Loupiac.

WHERE TO STAY

In the heart of the Entre-Deux-Mers vineyards and forests, this ancient fortified château dates back to the 13th century. But the present owners, the Bellanger family, could not be more modern when it comes to welcoming wine tourists to their home. Apart from tastings, wine and food pairing experiences, cooking classes and a guided naturalist tour, you can stay overnight in their luxurious guest suite, La Maison de Léo.